Lead artist: Lance Gharavi

Production Design: Anastasia Schneider & Brunella Provvidente

Choreographer: Eileen Standley

DJ: Sonique De Fleurs

Lighting Design: Joh Aho

Media Design: Jake Pinholster

Storytellers: Brian Foley, Jamie Haas Hendricks, Julie Rada, Joya Scott, Megan Weaver

Scribes: Caitlin Castro, Jeremiah James, Filip Kovasevic, Cameron Mundo, Mandy Nielsen, Michaela Woodridge

We see you. We hear you.

Tell us your story.

Twitter Verses was performed over a period of three days in multiple locations, real and virtual.

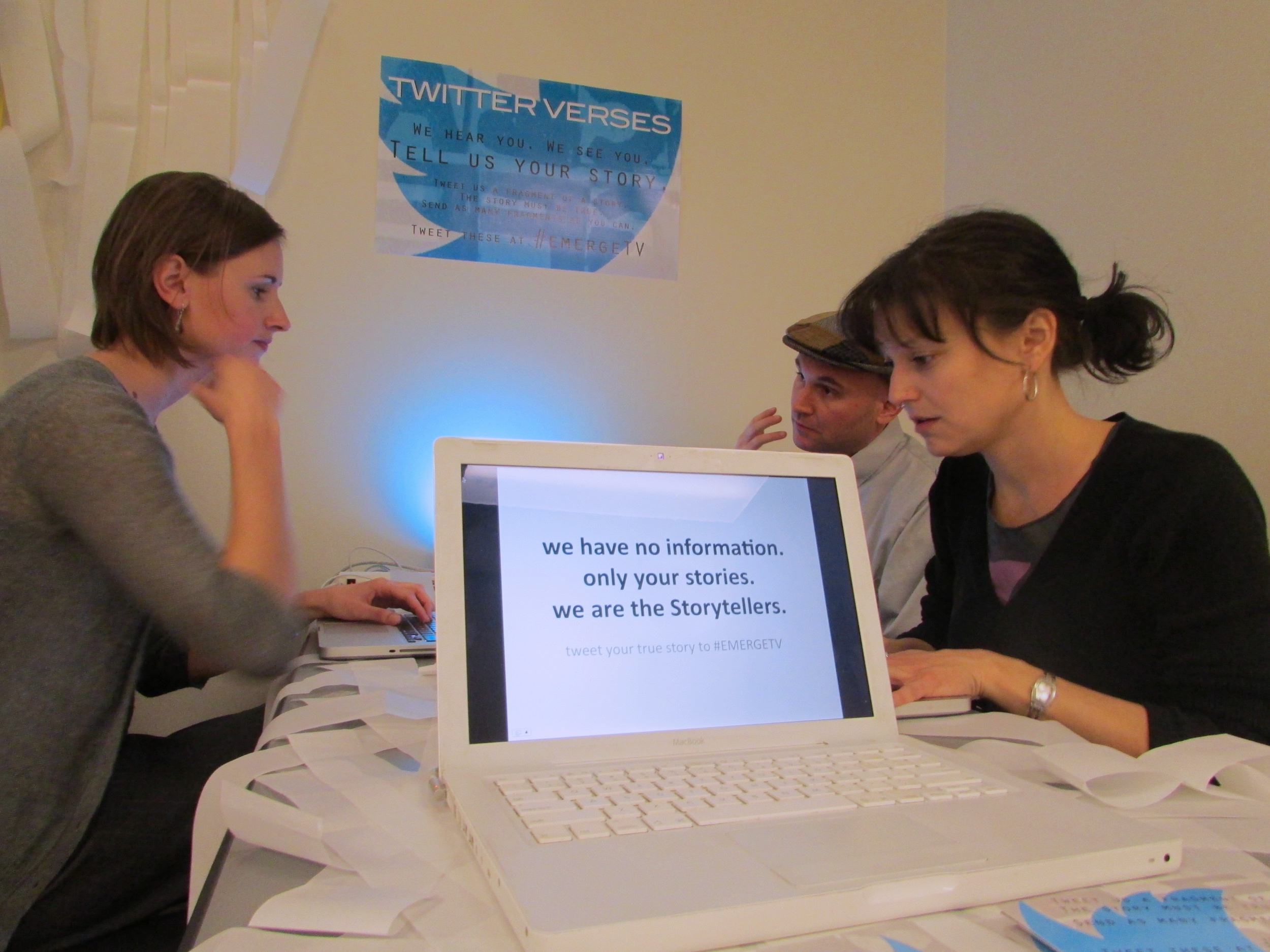

One week before the start of the performance, we sent out messages via social media, as well as old-fashioned word of mouth and club fliers, inviting the public to collaborate in the creation of Twitter Verses. “We see you. We hear you. Tell us your story,” the message said, with the barely concealed creepiness of post-9/11 surveillance and confessional culture. “Tweet us a fragment of a story. The story must be true. Send as many fragments as you can.”

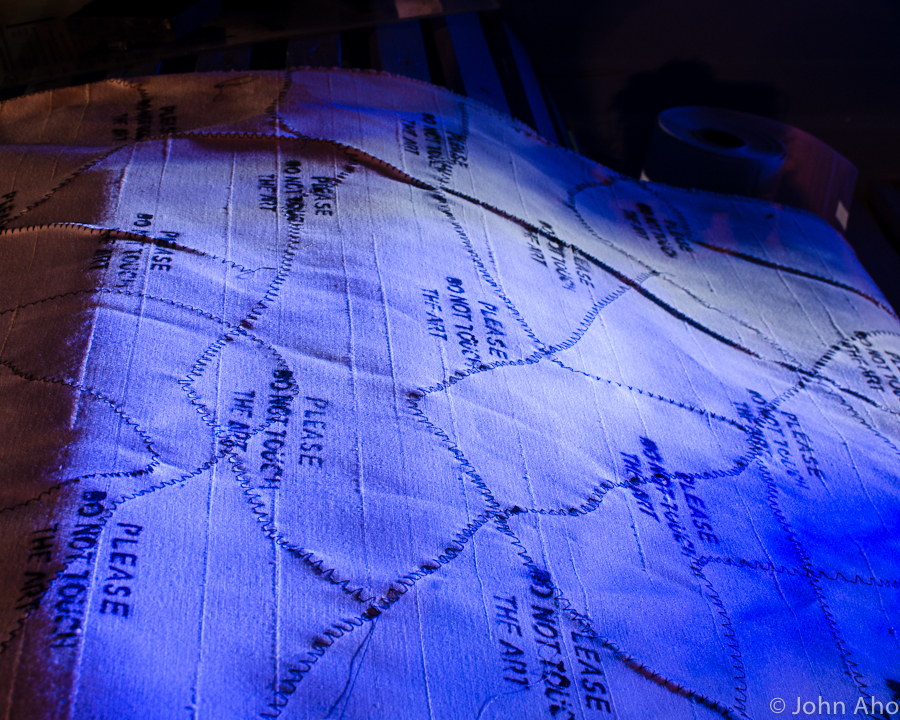

Over the course of three days, a group of three “Storytellers” sat in public, weaving these fragments together to form a single narrative. Meanwhile, a team of “Scribes” printed the emerging story onto the sidewalks using simple, impermanent paint. As the days went by, the writing became more and more obscured by traffic and the elements. The work of the Storytellers and Scribes was a kind of writing as performance. Twitter Verses produced an artifact that, like performance itself, was ephemeral and defined by its disappearance. The story slowly unfolded across ASU’s campus, tracing a long and twisting path that ended in the public plaza where the final act of Twitter Verses would take place.

Jean-François Lyotard said we live in an age that has moved past “grand narratives.” The idea of Progress, especially as achieved through science and technology, is one such grand narrative. Narratives are constitutive of social reality. Grand narratives are world creating, produced, maintained, and spread to serve the interests of power.

In our presumably post-grand-narrative age, many celebrate the proliferation of small narratives. All is decentralized and democratized, and the means of narrative production are in the hands of the people. This is a significant idea behind web 2.0. It is a move from vertical to horizontal, from tree to rhizome, from archive to wiki. Twitter is a notable example of where culture is thought to be moving—all is decentered and multi-vocal. Significantly for all our talk of power, it has been an instrument some have used to help overthrow forces of centralized oppression. In this new model, everyone has a voice. We move through a universe of stories. An immense cloud of verses.

That’s the story, anyway. But how reasonable is such utopianism?

Twitter Verses was a way of addressing this question. It was about our ages-old anxieties regarding “the one and the many,” an ancient and occult problem worried over by philosophers since before Plato, and still puzzling today’s scientists working at the cutting-edge of physics. Is there one thing? Or many things? One story? One truth? One reality? One universe?

Or many?

The tweeting in Twitter Verses celebrated the many stories and the optimism of postmodern digital culture: our excitement about the future and our utopian fantasies of the many.

But there are the Storytellers, who weave together into a single story the thousands of tweets from the public, and the Scribes who print the story onto sidewalks. The Storytellers aren’t modernist geniuses inventing tales from their own imagination; they simply turn the many into one. They compose a new kind of master narrative. They create the story—the one story to rule them, one story to find them. In Twitter Verses, that story was literally inscribed across an educational institution, upon the very ground beneath our feet, to be consumed by our young people and by our intelligentsia. It formed, in quite a literal sense, a foundation. The Storytellers composed this new social reality from the raw material the public gave them; the Scribes were merely ciphers, disseminating the narrative fed to them. Are they our media, our educators, our bosses, our entertainers? The Ideological State Apparatus?

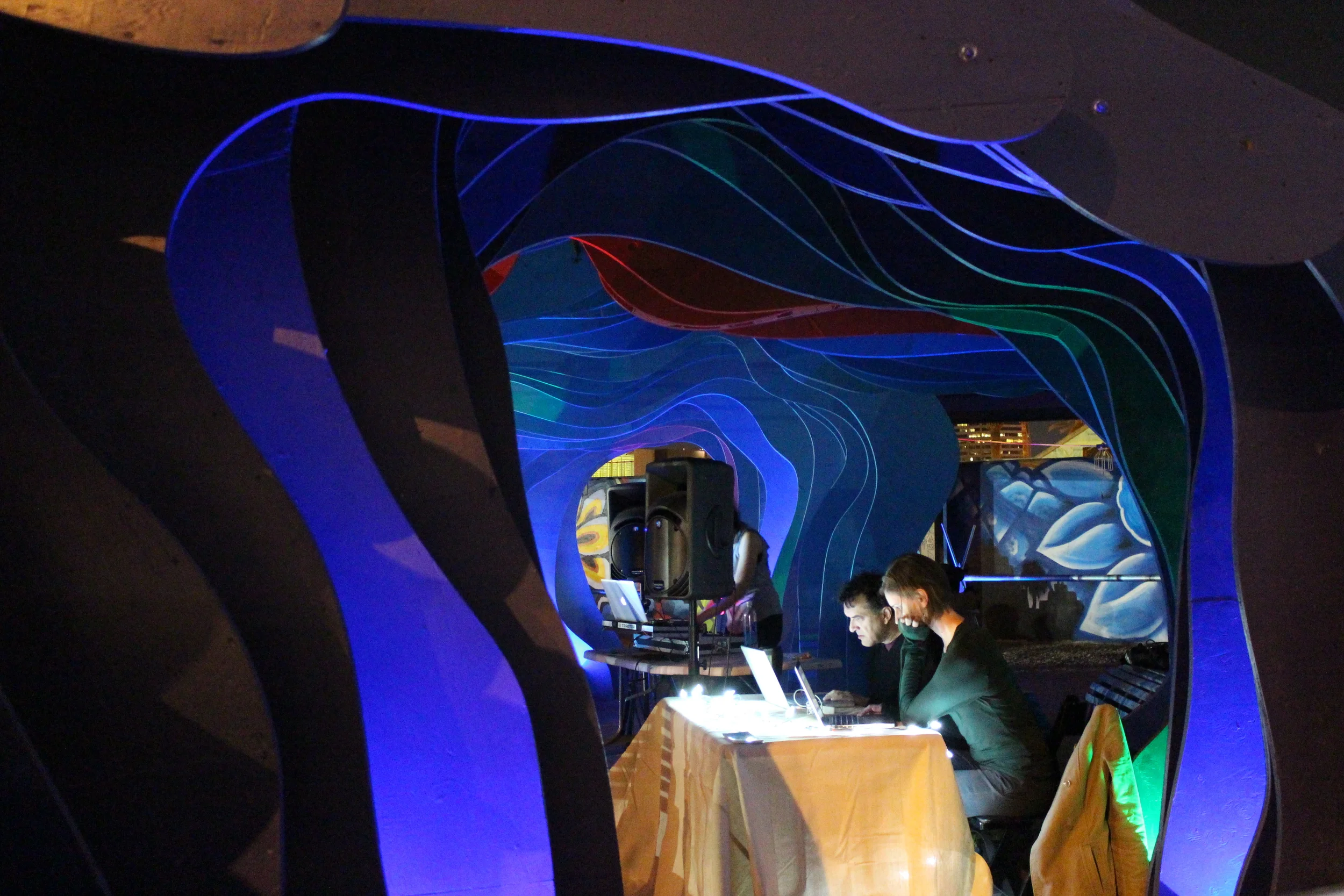

In the final act of the "play," a spoken word performer spit this story rhythmically into a mic accompanied by dancers and an alluring groove laid down by a DJ. The story must always be alluring, of course. Whether it is hopeful or fearful, it is always alluring. The DJ is there to help make it so. This is how stories work. There is always the many and the one. And the one must always seduce us.